Fundamental Technology Research Center

Research & Development Center

Innovation & Technology Division

YANMAR HOLDINGS CO., LTD.

YANMAR Technical Review

Ergonomic Evaluation for Yanmar Products

Aiming to Improve Usability

Abstract

This article describes Yanmar's work on the ergonomic evaluation of human-machine interfaces (HMIs) in its industrial vehicles and boats. To ensure consistent data acquisition, Yanmar developed an operating simulator that reproduces dynamic work environments, enabling this work to deal with challenges such as environmental fluctuations and seasonal constraints. The simulator is the world's first multi-vehicle and boat operating simulator equipped with advanced features including physical simulation, omnidirectional visibility, and multi-scenario HMI adaptability. Case studies presented in the article describe the optimization of lever layout to reduce physical loads and an evaluation method for developing intuitive HMIs. The former utilized the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) ratio, a value calculated from electromyography (EMG), and HMI development used eye-fixation-related potential (EFRP), a value derived from electroencephalograms (EEG). Yanmar uses these technologies in its development of user-friendly products.

1. Introduction

Yanmar seeks to supply machinery that is easy for anyone to operate, regardless of age, gender, body size, or experience. When operating a machine, the human-machine interface (HMI) is used to pass human inputs to the machine and to obtain information back. Because the HMI stands between the machine and human, optimizing its design is essential if machines are to be safe and easy to use.

As industrial machines are a means of production, the focus in the past has been more on function and performance than it has been on the HMI. For this reason, work on HMIs has tended to be limited to sensory evaluation and the review of previous models. More recently, however, ease of operation has become an important factor not only in extracting the maximum functionality and performance from the machine, but also as a means of differentiation from competing products. Accordingly, rather than relying only on sensory evaluation and the review of previous models to improve its HMIs, Yanmar has also been performing quantitative assessments using objective indicators that take account of human characteristics to create safe and easy-to-use interfaces that are optimized for human.

HMIs in industrial machinery such as agricultural or construction machinery differ significantly from those in the automotive industry. In addition to a steering wheel and pedals, levers and switches are also used to operate these machines and their meters and displays need to convey extensive information that relates both to driving the vehicle and operating its equipment. That is, HMIs cover a wide range of both controls and displays. Given the increasing number of elements that go into the more sophisticated functionality of today’s machines, HMIs are also growing in complexity. In addition to ergonomic considerations, such as whether the size and shape of the controls in these complex HMIs are a good fit with the operator’s hand and whether they are positioned within easy reach, it is also necessary to consider how intuitive the HMIs are to use. This includes things like making the operation of controls readily apparent and positioning them in a way that avoids confusing the operator, even on machines with complex HMIs.

This article describes a test environment that assists with the development of HMIs like this that take account of human characteristics, explaining how it was constructed and presenting examples of its use.

2. Construction of Evaluation Environment: Development of Multi-vehicle and Boat Operating Simulator

The testing of HMIs requires systematic acquisition and statistical analysis of data from a dynamic environment that approximates actual working conditions and using a wide variety of test subjects with different characteristics, such as age, gender, body size, and level of experience. This involves collecting and analyzing data from an environment that is controlled in a way that provides the measurement conditions specific to each test. When data is obtained from an environment that is not controlled in this way, the standard error tends to be higher and therefore a large amount of data is required to obtain reliable analysis results. When data is obtained from a controlled environment, in contrast, less data is needed to obtain reliable analysis results, thereby reducing how much time and effort need to be spent on testing.

Driving (operating) simulators are commonly used to perform vehicle HMI testing in a dynamic environment. These are systems that replicate actual driving conditions and are widely used in applications such as automotive development(1).

As a driving simulator intended for industrial vehicles needs to simulate the operation of vehicle equipment as well as driving, it also needs to be able to replicate how this equipment works, vehicle behavior, and the behavior of the soil or other material with which the machine is working.

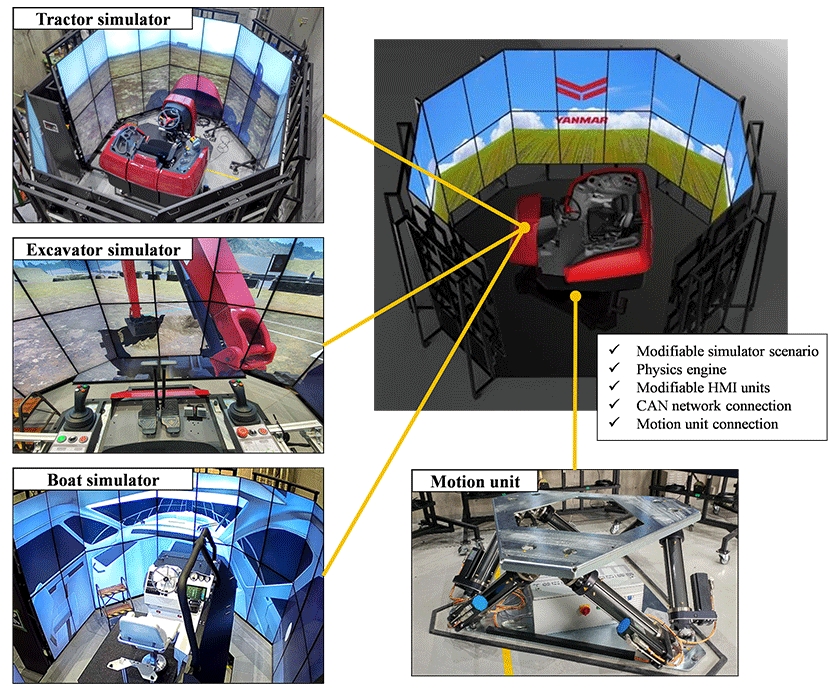

Yanmar has developed an operating simulator with these capabilities (Figure 1). Table 1 lists a comparison of its functions with those of a conventional automotive driving simulator.

Our operating simulator is equipped with the following main functions to simulate environments in which industrial vehicles or marine vessels operate.

- Physics engine: Replication of complex physical phenomena such as the behavior of the soil being cultivated or excavated or changes in the level of the water surface due to waves.

- Field of view: Replication of the 360° view of surroundings needed for machine operation.

- Support for using HMIs in a wide range of scenarios: Simulation encompasses locations such as farmland, civil engineering or construction worksites, and the ocean. Also, replication of the vehicle or vessel HMI.

As indicated above, the driving simulator enables the ergonomic testing of HMIs for both industrial vehicles and boats, having been developed to replicate both driving and working scenarios and having the ability to deal with minor modifications in an environment that eliminates noise (data variability) and does not require large amounts of testing time or other work. As an operating simulator suitable for a wide variety of both vehicles and marine vessels, it is a world first.

Table 1 Comparison of Driving (Operating) Simulator Functionality

| Function | Industrial vehicle/Boat | Automotive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle model | Driving model | ○ | ○ |

| Equipment operation model | ○ | - | |

| Physics engine | Resistance to driving | ○ | ○ |

| Soil behavior | ○ | - | |

| Fluid behavior | ○ | - | |

| Field of view | 360° | Forward view (in most cases) |

|

| Scenarios | Roads | ○ | ○ |

| Rough terrain | ○ | - | |

| Ocean | ○ | - | |

| Weather | ○ | ○ | |

| Hardware | Changes to HMI elements | ○ | ○ |

| Cockpit modifications | ○ | - | |

3. Applications of Ergonomic Evaluation

This section presents example applications of HMI ergonomic evaluation. The first example involved the formulation of HMI design guidelines based on quantitative assessment of how physically straining controls are to use. The second utilized the dynamic environment provided by the operating simulator to compare HMIs based on quantification of how intuitive they are to use.

3.1. Use of Electromyograms to Assess Ease of Operation and Formulation of HMI Layout Guidelines

The positioning of levers can be a major factor in how much physical load is experienced by machinery operators. If a lever is hard to use due to poor placement, height, or angle, the extra load it places on the arms or shoulders becomes a cause of fatigue.

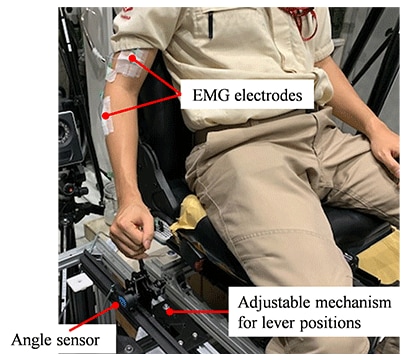

How easy a lever is to use can be assessed using an electromyogram (EMG). This is done by calculating the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) ratio from the EMG. The MVC ratio expresses the degree of muscle contraction in terms of electrical potential as a percentage of the value for maximum muscle contraction. The higher the value, the greater the load on the muscle.

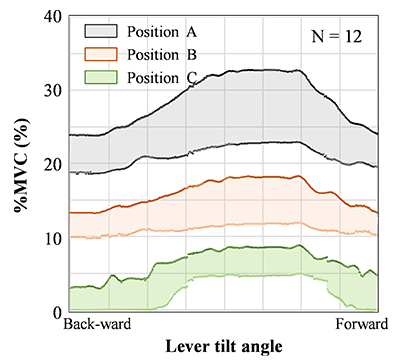

A systematic study was conducted in which the lever was placed at several different locations and the MVC ratios of 12 participants with different body sizes measured for each lever position (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows example results showing the variation in the MVC ratios obtained for three different lever positions.

It is known that MVC ratios are low when the lever position is compatible with natural arm movement (Position C in Figure 3) as this indicates a low level of muscle load. A guideline was formulated for designing optimal layouts that utilized this data and worked by mapping the integral of the MVC ratios obtained when operating the lever in each location.

3.2. Development of Method for Quantifying How Intuitive an Interface is to Use Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) (Eye-Fixation-Related Potential)

In addition to reducing physical stress, it is also important that the complex HMIs used in industrial vehicles are laid out in an intuitive way that makes it readily apparent how they are used. If the HMI lacks an intuitive operation and layout, the machine places greater mental stress on the operator by forcing them to think twice before operating the controls.

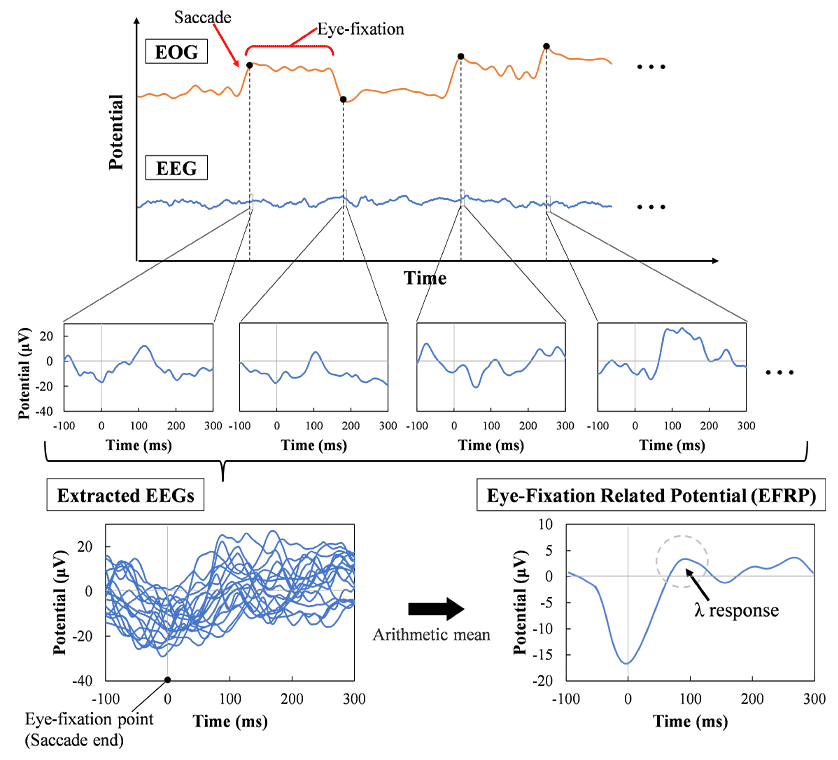

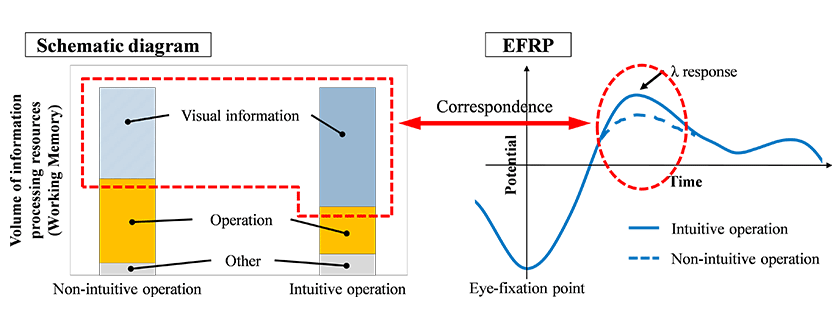

The method adopted for assessing how intuitive an HMI is to use involved eye-fixation-related potential (EFRP), a transient feature found in brain waves. An EFRP arises when eye-fixation occurs (when the subject’s visual attention lingers on a particular object) and is known to be indicative of visual information processing taking place in the brain(2). EFRP can be measured by simultaneously recording eye movement (by means of an electrooculogram (EOG) or similar) and electroencephalogram (EEG). However, the transient changes in the electrical potential of EEG are very tiny and are difficult to identify from a single waveform, being embedded alongside the brain’s underlying alpha rhythm and other electrical noise. To overcome this, the EFRP is determined in a way that smooths out the alpha rhythm, noise, and other signals that are present. This is done by taking the arithmetic mean of multiple waveform measurements obtained from the point in time when a trigger occurs and under conditions when a transient component should be present. Figure 4 shows how the EFRP is calculated. The EFRP trigger is the time at which the saccade eye movement stops, called the eye-fixation point. The arithmetic mean is calculated using the EEG data from this point onwards, adjusted to align the phase. The amount of visual information processing taking place in the brain (working memory) can be obtained by comparing the amplitude of the lambda response, a distinctive positive peak in potential that occurs in the EFRP waveform.

An operator driving a machine experiences a variety of information processing, dealing not only with visual information, but also with information relating to the spatial task being performed. Figure 5 shows a diagram of how EFRP relates to this information processing resource. If an HMI has an intuitive layout, less information processing is needed to operate it, freeing up more resources for processing visual information. This manifests as the lambda response having a higher peak potential(3). In other words, measuring the lambda response potential provides an indirect assessment of how much information is being processed to operate the machine (indicating whether or not its HMI is intuitive to use).

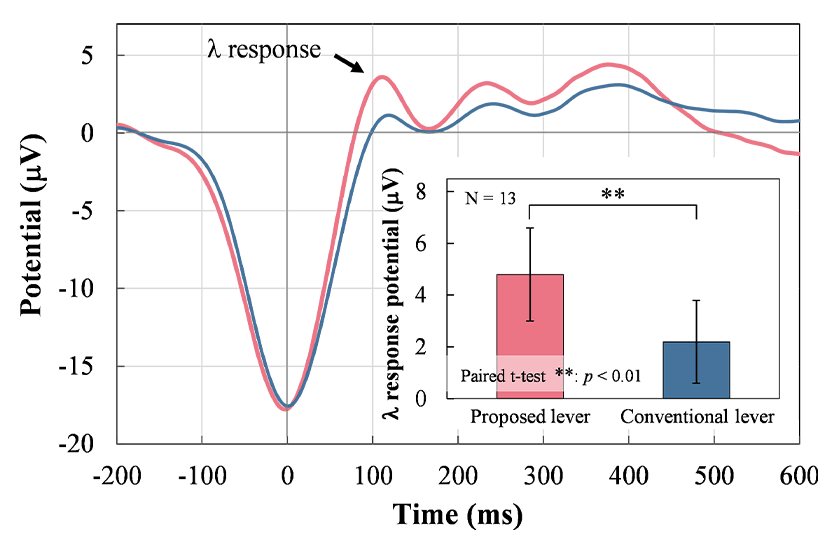

The technique was used on a tractor to verify whether it provides a viable way to quantify how intuitive an HMI is to use(4), (5). The HMIs being tested were a conventional main gear lever and a multi-function lever in which the main gear lever is also equipped with functions for forward/reverse and for engaging the sub-transmission. The multi-function lever is intuitive to use because it combines all the operations for vehicle movement in a single lever. A trial with 13 participants used a dynamic environment provided by the operating simulator (Figure 6) to compare how intuitive the two levers were to operate. Figure 7 shows EFRP waveforms obtained from test subjects using the two levers and their lambda response potentials. The lambda response potentials for the multi-function lever were higher than those for the conventional main gear lever by a statistically significant margin. That is, the results indicate that less information needed to be processed to operate the multi-function lever and more resources were used in the processing of visual information.

4. Conclusions

This article has described the following work undertaken for the ergonomic testing of industrial machinery HMIs.

- A multi-vehicle and boat operating simulator was developed that can replicate the conditions under which different products operate, thereby enabling ergonomic evaluation to be performed in a controlled environment.

- HMI layout guidelines were formulated and testing conducted on new HMIs by quantifying how easy and intuitive they are to use. This was done using objective indicators calculated from physiological measurements such as EMGs and EEGs.

HMIs play an important role in making products safe and easy for customers to operate. Yanmar intends to utilize the technology described in this article in product development as it strives to deliver better products to its customers.

参考文献

- (1)Y. Suda, Y. Takahashi and M. Onuki, “Universal Driving Simulator for Research,” Transactions of Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, Vol. 59, No. 7, pp. 83-85 (2005) in Japanese.

- (2)A. Yagi, “Saccade size and lambda complex in man,” Physiological Psychology, Vol. 7, pp. 370-376 (1979).

- (3)Y. Takeda, N. Yoshitsugu, K. Itoh and N. Kanamori, “Assessment of Attentional Workload while Driving by Eye-fixation-related Potentials,” Kansei Engineering International Journal, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 121-126, (2012).

- (4)N. Yoshioka, T. Kimura, Y. Shu, T. Okamatsu, N. Araki and M. Ohsuga, “Evaluation of the Tiller Switch Layout of a Tractor Using Eye-Fixation Related Potentials,” The 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC 2020), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20-24 Aug. 2020.

- (5)N. Yoshioka, T. Okamastu, Y. Shu, N. Araki, Y. Kamakura and M. Ohsuga, “Evaluation of the Effect of Different Operating Methods on Operability in Excavator HMI,” The Japanese Journal of Ergonomics, Vol. 61, Supplement, p. 3 D05-02 (2025) in Japanese.

Author